Interactions between the oceans and bodies of glacial ice are governed by many physical processes that operate a broad range of temporal and spatial scales. Among a few examples are interactions between ice shelves (floating extensions of ice sheets) with the ocean circulation in sub-ice-shelf cavities and interactions between ice shelves and ocean waves.

Interactions and feedbacks between ice shelves and the ocean circulation

Ice shelves are formed by the glacial ice that is thin enough to lose its contact with the underlying bedrock and to float into the ocean. Almost three quaters of the Antarctic grounded ice are fringed by ice shelves. The ocean circulates in the cavities formed between the bedrock and ice shelves and causes ice melting or refreezing. The thermodynamic and mechanical processes in the ice shelf-ocean system are tightly linked: changes in melting/freezing at the ice shelf-ocean interface affect ice flow by changing the ice-shelf thickness that controls the ice-shelf flow. The same changes affect the ocean circulation beneath the ice through the effect of melting on water density and on the shape of the ice-shelf base that steers the buoyancy driven circulation in the cavity.

Formation of sub-ice-shelf melt channels

These tightly coupled interactions and feedbacks between ice shelves and the ocean circulation in their cavities are manifested in the formation of melt channels that are widespread at the base of many ice shelves and detected in remote sensing observations and in situ geophysical surveys. Results of numerical simulations of a coupled ice-shelf/ocean-circulation model show that they are a direct product of a dynamic coupling between the ocean circulation in the sub-ice-shelf cavity, sub-ice-shelf melting and the ice-shelf flow (Sergienko, 2013). The fresh and cold water formed as a result of melting is much lighter and more buoyant than the ambient ocean water. As soon as it forms, it starts to float along the ice shelf base, which shape determines how fast it can flow – the steeper the ice-shelf base, the faster the meltwater plume can flow. In its turn, the rate of sub-ice-shelf melting strongly depends on the buoyant plume speed – the faster it flows, stronger melting is. Hence, there is a positive feedback between the plume flow, the shape of the ice-shelf base and melting.

The shape of the ice-shelf base depends on how wide the ice shelf is and how much shear it experiences at its lateral boundaries. With a strong shear, the base is relatively steep. That means that the channels can form spontaneously on ice shelves or their parts experiencing lateral shear. Once formed, melt channels are advected with the ice-shelf flow, and their shape is determined by the balance between sub-ice-shelf melting and the ice-shelf deformation. Because the ocean and meltplume flow is affected by Coriolis force, the shape of the channels is not symmetric. They are much steeper on the side where the plume is diverted by Coriolis force (the left side in the Southern Hemisphere). The temporal evolution of the channels can be due to the internal variability of the ice-shelf/cavity system due to its feedbacks. The presence of the channels affects the stress regime of the ice shelves and they could potentially promote formation of the fractures and crevasses.

Impacts of the ocean conditions on ice shelves and their cavities

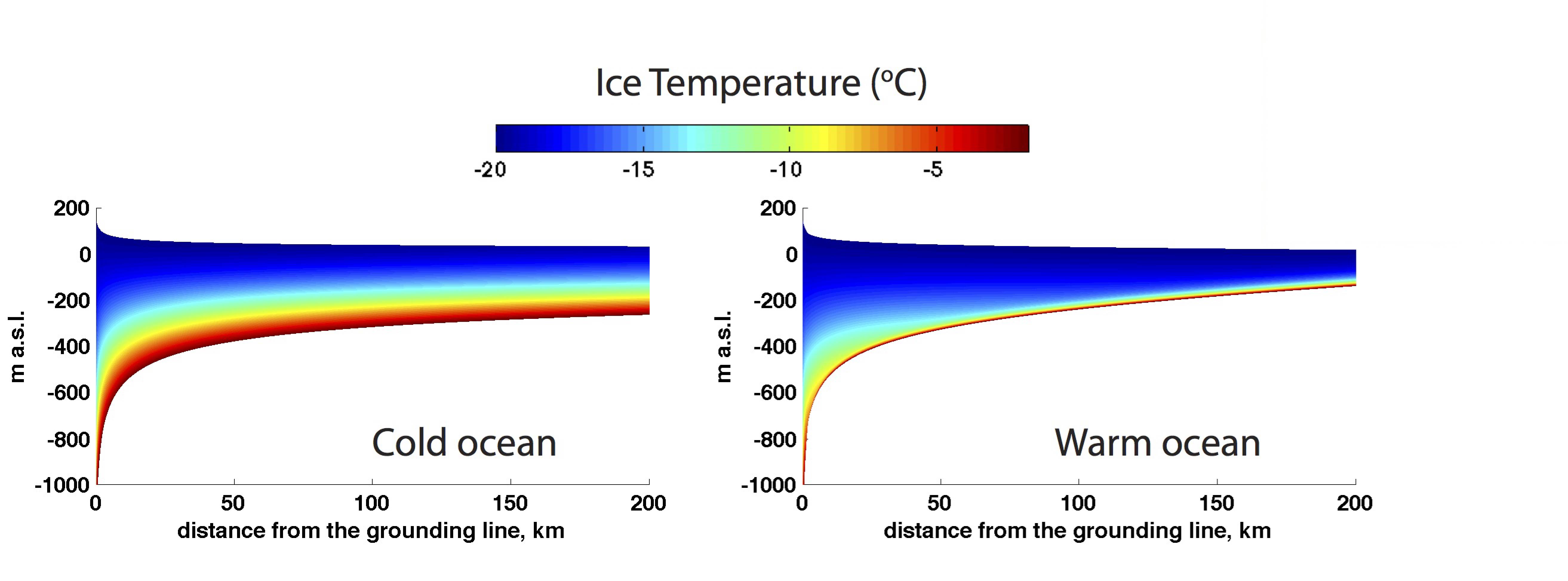

Results of our other study (Sergienko et al., 2013) show that there is a strong relationship between the shape of a sub-ice-shelf cavity and melting at the ice-ocean interface. Our results also show that the temperature of the ocean has strong effects on the temperature of the ice. In the case of relatively cold ocean conditions, such as observed under the Filchner-Ronne and Ross ice shelves, ice shelves are much warmer, compared to the very warm ocean conditions observed under the Pine Island Glacier or George VI ice shelves. These counterintuitive results are due to the fact that when an ice shelf flows into a warm ocean, the warm ice that resides near the bed of an ice sheet is eroded by strong melting and colder ice fills the interior of the ice shelf. In contrast, when the ice shelf flows into a cold ocean, melting at its base is much weaker. Therefore it is thicker and warmer, because the warm ice near the bottom is not melted away.

Interactions between ice shelves and ocean waves

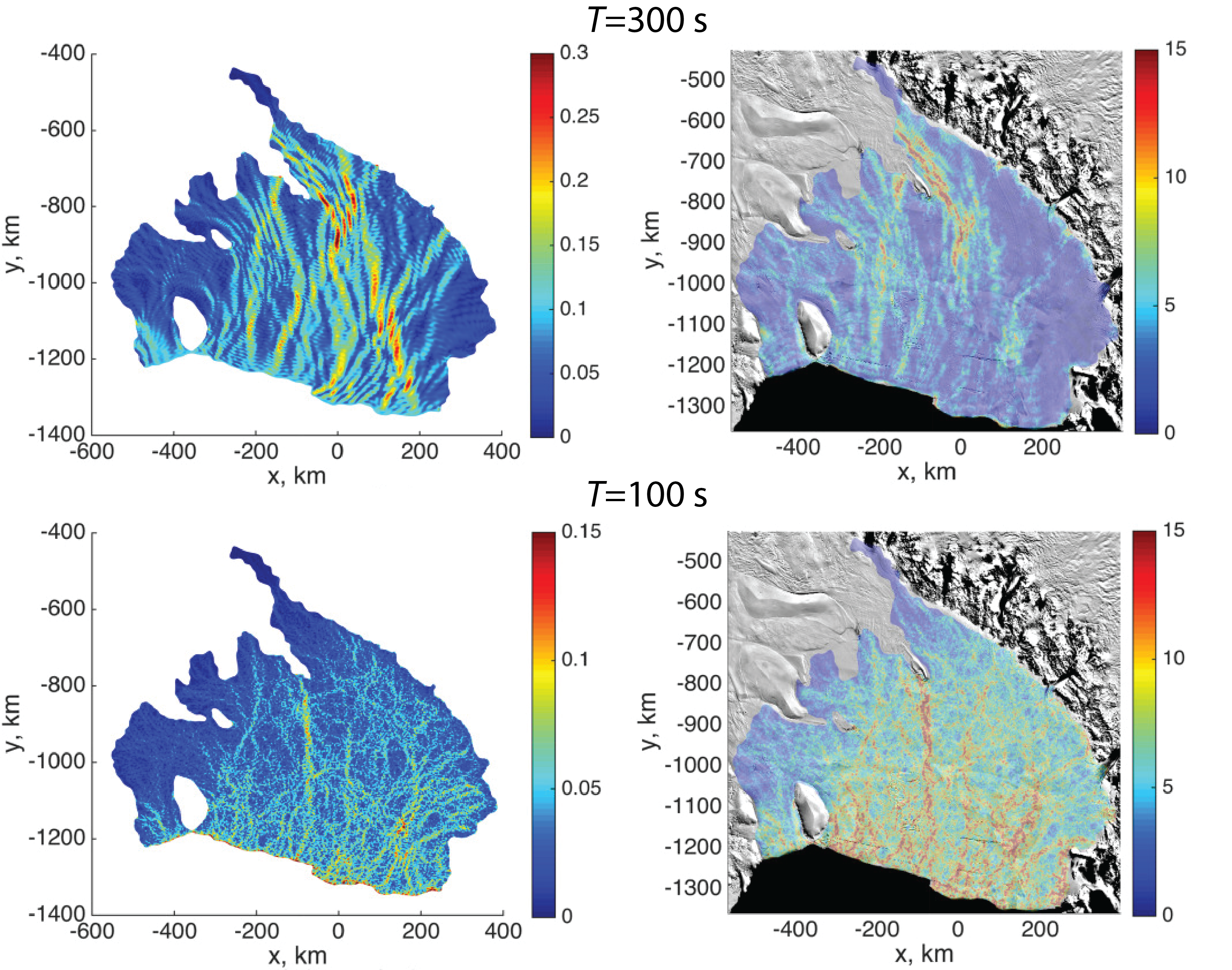

Ocean waves ranging from short-period sea swell to very long infragravity waves formed by cyclones and large storms continuously impact ice shelves. Sea swell mostly affects the ice-shelf calving front, and long-period waves can propagate into the cavity and excite ice-shelf flexure far away from the calving front. The associated flexural stresses can promote either existing fractures or develop new ones (Sergienko, 2010). The cyclic nature of the wave-induced stresses contributes to ice fatigue and damage that is also a precursor to ice shelf disintegration. The flexural gravity waves simultaneously propagate through the ice shelves and their cavities and can excite their normal modes (Sergienko, 2013) and affect the ice-shelf stress regime.

The shape of the cavities determined by the ice-shelf bathymetry and the ice-shelf thickness have strong effects on the propagation of the flexural gravity waves. Analysis of such waves on the Ross Ice Shelf shows that they propagate as concentrated beams (Sergienko, 2017). The direction of these beams is determined by the incident angle of the waves in the open ocean; the width is determined by the period of the incident ocean waves. The higher frequency ocean waves cause larger flexural stresses, while lower frequency waves can propagate farther away from the ice-shelf front and cause flexural stresses in the vicinity of the grounding line. In some instances when frequencies of incident ocean waves are close to the ice-shelf eigenfrequencies, the ocean waves can excite normal-mode oscillations in ice shelves.